Collecting birch sap for mineral water, wine, beer, vinegar and syrup

The Sap is rising (17th March 2016)

…Or is it? (17th March 2018))

I’ve a confession: although my long-standing interest in wild food cookery does add incredibly wild and nutritious versatility to my daily menu with respect to rich soups, unique salad combinations and intriguing side vegetables – all very health promoting and worthy; truth be told, I’m actually somewhat of a sugar addict. Yet, for the most part, sweet wild foods are associated with the abundant fruitfulness of summer and autumn – apples, pears, cherries, blackberries, bilberries, mulberries etc, and as delicious as such fruits are in their unprocessed state or as fruit leathers, their sweetness is invariably counterbalanced by varying degrees of acidity. Hardcore, unadulterated and non-toxic sweetness is actually quite hard to come by in the natural world, at least where I live in the South East of England. Here sugar maple Acer saccharum sap, as well as the syrup or crystaline sugar prepared from it, is hard to obtain, as is the even more intriguing sugar lerp preparations of the wonderfully inovative Pascal Bauder in California. Indeed if you’re an American or Canadian and looking for some useful information on tapping sugar maples, you may learn something of interest here, but best to check out some other sources that specifically detail that process. These are good:

Maple syrup production for the beginner, Making Maple Syrup, Backwoods Home Magazine, Tap My Trees, Small Batch Maple Syrup Making.

And yet here in the United Kingdom, from as early as the final week of February (Southern England) until as late as the end of April (Scotland), and with a similar early to later coming of the spring across the different states of the US, that hardcore sweetness lies quite literally in untapped abundance, residing in diluted form within the trunks of some of our commonest trees: Birch (Betula species), Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), Field Maple (Acer campestre), Lime (Tilia species), Walnut and various others. All, in theory, can be successfully tapped for their sap, the first two providing the best results in my experience. Birch, especially, is fail safe! For the purpose of this article then, ‘sap’ refers to birch sap unless otherwise stated. Howerver, before getting down to discussing that, and the all important question of, “but why bother tapping trees for sap in the first place?” let’s briefy look at other trees to tap.

Trees And Other Plants That Can Be Tapped For Sap

Four good sources of information about this that I’ve come across are The Plants For A Future database, The Agroforestry Research Trust, the website Wildfoodism, and my own random walk abouts with a sharp knife and curious mind.

The Agroforestry Research Trust has a useful pamphlet giving details of many trees that can, potentially, be tapped. It only costs £1:

https://www.agroforestry.co.uk/product/factsheet-s07-edible-tree-saps/

Including even more species than the above factsheet, is the highly informative Plants For A Future Site. The database details 80 different plants, mostly trees, but also shrubs, vines, and herbaceous plants from which an edible sap can be obtained. The species or genera involved include not only the more well-known Acer (maple), Betula (birch), Jugulans (walnut), and Carya (hickory) species, but also Pinus (pine), Alnus (alder), Larix (larch), Populus, Eucalyptus, Agave, Fushia, Hydrangea, Platanus, Rubes, Actinidia, Eleocharis, Jubaea, Nothofagus, Paederia, Parthenocissus, Prumnopitys, and Ripogonum. This is really useful information, and can certainly help focus ones explorations if one wants to make sap discoveries beyond the obvious maples and birches.

https://www.pfaf.org/user/DatabaseSearhResult.aspx

The Wildfoodism website, while sticking mainly with the better know sap-tapable genera of Acer, Betula, and Jugulans, provides some additional information on flavour and sugar content. It mentions 22 different tapable trees:

Sugar maple (Acer saccharum), Black maple (Acer nigrum), Red maple (Acer rubrum), Silver maple (Acer saccharinum), Norway maple (Acer platanoides), Boxelder (Acer negundo), Bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), Canyon maple, big tooth maple (Acer grandidentatum), Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum), Gorosoe (Acer mono)Butternut, White walnut (Juglans cinerea), Black walnut (Juglans nigra), Heartnut (Juglans ailantifolia), English walnut (Juglans regia), Paper birch (Betula papyrifera), Yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), Black birch (Betula lenta), River birch (Betula nigra), Gray birch (Betula populifolia), European white birch (Betula pendula), Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), Ironwood, hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana).

https://wildfoodism.com/2014/02/04/22-trees-that-can-be-tapped-for-sap-and-syrup/

My somewhat random and inconclusive explorations in the garden nevertheless revealed some interesting discoveries. The inconclusive nature of the exploration comes from the fact that although, at the time (12th March 2018), silver birch sap was in full flow, it could be that some of the species tested would have produced a good sap flow either earlier or later in the season, or perhaps not. I tested:

Indean Bean Tree, Service Tree, Goat Willow, White Willow, Lime, Hawthorn, Red Oak, Pedunculate Oak, Sessile Oak, Black Poplar, Apple, Rosa multiflora, Himalayan Honeysuckle, Fushia, Horse Chestnut, Sweet Chestnut, Hazel, Wysteria, Ash, Rowan, Black Mulberry, Larch, Beech, Cutleaf Japanese Maple, Japanese Flowering Quince, Grape (Vitis vinifera and Vitis coignetiae), Porcelain Vine (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata var.

Climbing Hydrangea: Hydrangea anomala

Climbing Hydrangea sap collection

Climbing Hydrangea sap collection

The most interesting personal discovery was from the tree I enjoyed collecting the ripe fallen fruits from in late summer, the Cornelian Cherry. This is a member of the Dogwood genus, but I can find no reference to sap being collected from it. Although it has been in blossom for 2 weeks, its sap flow is still quite forceful, dripping at about half the rate of birch.

Fallen fruit

Collecting fallen fruit

Pulping the raw cornelian cherries to remove the stones.

Cornelian Cherry dripping sap

Bottle-collecting sap from Cornelian Cherry

Unidentified tree, sap collection.

What does one do with such sappy opportunities? One makes Seven Sap Syrup, and updates this blog whilst sipping a Sappy Seven, of course!

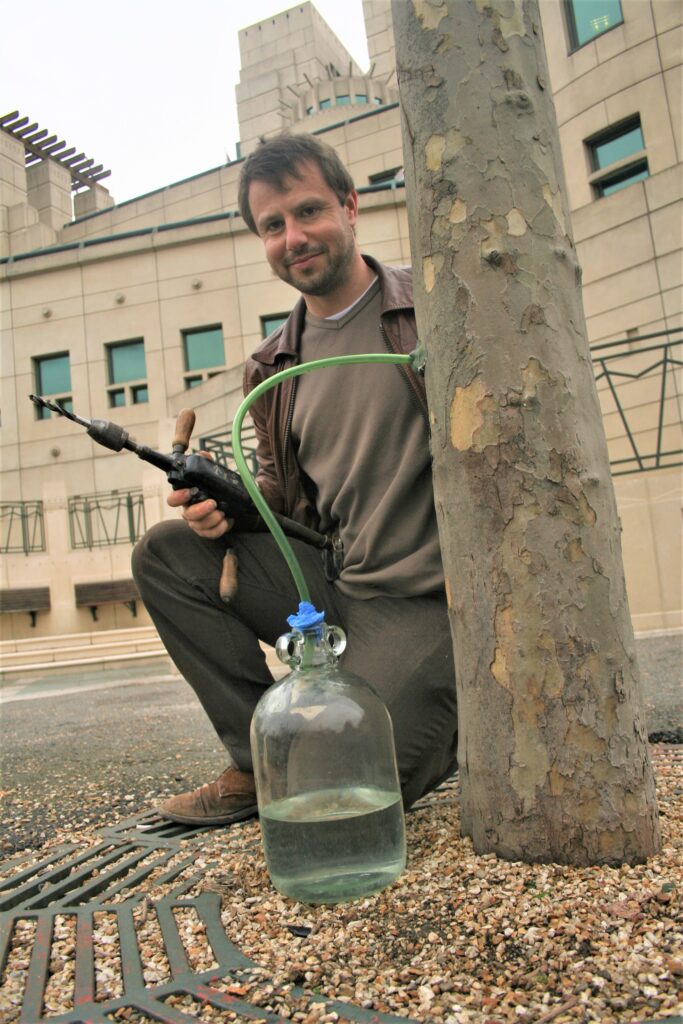

The photo in this picture, of me tapping London Plane Trees outside the Houses of Parliament in London whilst wearing a dodgy 70s leather jacket, and carrying a hand drill around as if it’s a gun, takes us smoothly into the next section: Where to tap?

Where To Tap And Where Not To Tap!

As with foraging generally, unless you are foraging around your own home, the most considerate thing to do, and often, but not always, the approach that causes least problems is to ask permission from the land owner. I think this is likely to me more readily obtainable as regards sap collection if you go for the more gentle method of tapping the end of a branch.

The images below from 2010 show me exploring an idea at the edge of absurdity and extreme. I wanted to discover what would happen if I tapped without permission in one of the most inappropriate places possible. Two places were chosen: Right outside The Ministry of Defense in London, and very near to The Houses of Parliament (note: no trees were actually drilled, so I wasn’t really foraging, just pretending to). This was with a view to writing an article about foraging and the law (which I still haven’t got around to writing). The result here was wonderfully and dramatically predictable: Two flanks of battle-ready police coming at me from two directions. To their credit, as I did my best to act like a clueless idiot, they were very good natured about it all. Still, I could have potentially been shot. Bottom line: get permission and tap trees in a woodland, hedgerow, open fields or your own garden.

Apart from playing at daft games to explore the negative consequences of not getting permission, I have always wondered if sap can be obtained from London Plane trees, after all, the tree, Platanus x hispanica, is thought to be a hybrid of the Oriental Plane/Old World Sycamore Platanus orientalis and the American Sycamore Platanus occidentalis, and at least the latter is said to produce an edible sap. So far, I’ve not succeeded in getting any sap from this tree, but would love to hear from anybody who has had success in obtaining it. I can tell you though, that the very young spring leaves are great candied in maple syrup.

The All Important Question:

Why bother tapping trees for sap in the first place?

This is a question I’m frequently asked, quite often by people who have tried and have been disappointed that what drips from the tree tastes pretty much like water, not the sweet ambrosial nectar they had expected. Well, it’s a reasonable question I suppose. There are as many possible answers to this as there are theroies on the precise mechanisms that allow the sap to ride in the first place (this 34-page article makes interesting reading if you’ve ever puzzled over that question)…

Doing it the old way (drilling). Now I much prefer the less invasive method of tapping the end of a branch, as below. Details HERE.

……or, below, 10th March 2017, 12 °C

In the Ukraine and parts of Russia the sap is collected and sold as a type of mineral water, so they clearly value it. A fantastic, easy to make and reliable white wine can be made with a very distinct and pleasant taste, as well as beer, vinegar (see recipe at the end) and a rich caramel and molasses-like syrup. But, above all else, as with all foraging, it provides an excuse and opportunity to arrange your life according to the cycles of nature rather than the oppressive dictates of work routines and the terrible tick-tock tyranny of clock time or even traditional calendars. Each year I try to refine my understanding of when the sap flow begins and when it’s in full swing. This year it begun a day before the spring equinox, 5 days after reports that frogspawn was appearing in local ponds, and two days before the wood ants began to awake from winter slumber as they amassed to form new colonies. This is the realm of magic, awareness, and attunement, connecting with life, poetry and mystery, and clocks serve no purpose!

The sap then, which is actually about 95% + water, minerals and a little sugar, can be evapourated off to make a sublimely delicious if somewhat energy intensive syrup – it is the absolutely perfect accompaniment to elderflower fritters. In fact, the only near equivalent you can buy in this country is maple syrup. That is commercially viable because the ratio of sap required for a litre of syrup is 30:1, whereas for birch it is between 80 and 120:1 (I usually find that a 95:1 ratio is perfect for a rich dark and delightfully complexed flavoured syrup, whereas a 60:1 or 70:1 ratio makes for a satisfying and delicious but lighter syrup). But don’t let that put you off. Once you’ve tasted birch sap syrup, the effort required to make it will seem more than worthwhile. For those who are unconvinced there are several other excellent uses for the sap once collected as I’ll explain below, as well as various birch-related bushcraft skills to practice while the sap is simmering. First, though, how exactly is it obtained? There are several possible collection methods; here are just a couple.

Methods Of Sap Collection

Drilling into The Main Trunk And Using A Spile Or Plastic Tubing

I’ll describe this way first as it’s the most common practice, and one that I followed for many years, but would encourage you to try the branch method as described later. This trunk-drilling way is perhaps the most efficient, and least time consuming, and yet the consumption of time doing things less effieciently, but in a way that resonates more deeply with ones feeling, beliefs and values, has a lot to recommend it.

Between the end of Feb and mid-April when temperatures are usually between 0 and 15 °C – but especially in the second half of March, take a metre length of 0.5-1cm diametre plastic tubing or a spile (metal or plastic, although some people recommend non-metalic spiles for birch sap collection), a 2 or 4 litre plastic bottle (keep spare tops to put on the bottles when returning to pick up the sap – or just return with a large container), a drill with drill bit the same diametre as the plastic tubing or compatable with your spile diametre, a piece of tissue or cotton wool, a lump of plasticine (modeling clay) or natural clay, a wooden bung and a hammer. Select a suitably sized, well-established, and healthy looking tree (unhealthy trees don’t take so kindly to having more pressure put on them by the likes of me or you drilling a hole in them or cutting their branches!) – at least 8-10 inches across. Also, especially if in a woodland with lots of birch jostling for space and light, go for the trees with the largest crown of branches. These will have the best sap flow.

Before continuing, let’s look at some examples of both trees that are suitable for tapping and ones that aren’t:

This birch has a huge crown but looks sick.

It’s oozing sap and resin.

Multiple gashes ooze

It really is like blood. Betula sanguinius!

A birch oozing a mixture of resin and sap, best left to heal. Why do trees bleed?

The tree below looked very promising, a good size with an impressive crown. But what’s that weird growth? Bizarrly this looks very much like a young Amanita muscaria or Fly Agaric mushroom, often associated with birch, but not so often in this strange and mysterious way. Too wonderfully peculiar to tap! The last one had a great crown, but with that many (genuine) fungi growing on it is probably dead or dying.

And the following tree. Two days ago it was standing tall in the forest, but today it has fallen and is oozing sap at the break, but let’s look a little closer, the signs that it was not a healthy tree are there….

Fallen two day’s ago and oozing sap.

Closer inspection reveals a wound half way up the trunk..

…and it has clearly been losing some big branches, not a sign of good health.

The above tree, in fact, is very unlikely to live, and is in an area where it is likely to be cleared away, so a prime candidate for making richly coloured, aromatic, and bitter inner bark flour. For a unique flavour, this can be added in small quantities to regular flour when baking.

A very recently fallen birch with outer bark removed.

Scraping off the orange inner bark.

Bark shavings

Bark shavings

Birch bark flour

What about these? No, way too young and small……

But, all hail the perfect Silver Birch

and Paper Birch…..

To continue……. Mark a spot 2-3 feet up from the tree’s base. (In fact, you can tape a collecting vessel to the main trunk 15 foot up the tree if you don’t want it to be disturbed – useful if the trees are in an urban environment where your collection set-up might be tampered with lower down).

With the drill bit angled about 30 ˚ up from the horizontal (although straight in is fine too), drill a clean hole about 3-4 cms deep into the tree. Blow out bits of debris (close your eyes!). Liquid should drip from the hole within 10-20 seconds at the rate of 4 or more drops per second at the peak of sap flow. If not, hammer in a wooden bung or piece of clay and try another tree.

Push one end of the plastic tubing 1-2 cms into the hole so that it is held firmly in place. Place the other end into the collecting bottle, far enough in so that it can’t slip out. Gently pack tissue or cotton wool around the tube at the neck end of the bottle, allowing the air to escape as the bottle fills with sap and to prevent insects from getting in (you can just cut or melt holes into the top of plastic lids – but make sure it isn’t a completely tight fit as you need to allow air to escape from the bottle as it fills up). If using a spile, push and twist to firmly set it in the tree.

Make sure it is a tight fit, and that it is pushed in beyond the small round hole they have towards the narrow tapering end.

Scoop out a handful or two of soil at the base of the tree and place the bottle in the shallow hole created to prevent it falling over if using tubing, or if using a spile hang the bottle from the hook. As a precaution, to prevent any leakage, you can roll out and press a small piece of plasticine or clay around the tube or spile to make a perfect seal with the tree trunk.

Hanging bottle with spile on sycamore

hanging bottle with spile on sycamore

Spiled sycamore, glass bottle (I ran out of the others)

Leave for 12-48 hours, after which time the bottle will most likely be brimming with sap. Alternatively, you can use a small length of tubing or a small elder stick after clearing out the soft central pith, make your own spile,and allow the sap to drip freely into a collecting vessel such as a demijohn – preferably using a muslin covered funnel to direct the liquid and prevent insects falling in. In woods where there are wood ants, the ants will amass around any exposed sap.

Finally, plug up the hole to prevent infection of the tree, particularly from fungal spores. Hammer in a hard wood bung, firm piece of cork cut to size, some clay or, as a temporary measure, a piece of plasticine. Whatever I use, I always line it with fresh cherry resin. Resin production is a tree’s healing response to mechanical damage so is worth using. It also makes for a really good seal.

At this point it is certainly worth drawing your attention to the ‘to plug or not to plug’ debate going on right now, with some evidence suggesting that using a bung or plug may in itself disrupt the trees ability to heal itself or trap spores and microbes, leading to infection. Follow this link for an article exploring these issues that, helpfully, also documents (apparent) ‘best practice’ Some impacts to paper birch trees tapped for sap harvesting in Alaska

If in doubt, ask the tree.

If in doubt about asking the tree

Use your intuition.

If in doubt about using your intuition

Read (and apply the techniques) described in

Craig Holdrege’s Thinking Like a Plant

and Nathaniel Hughes and Fiona Owen’s sublime

Intuitive Herbalism.

In the past I have generally taken no more than about 8 litres per tree (when drilling), and only tap the same tree on alternate years. Nevertheless, some people will tap continuously from one tree throughout its entire period of sap flow, but only return to that tree every 4-5 years; others take 5 litres and return every year to the same trees. These days I always collect sap from the end of the branch. I asked the trees, it’s what they prefer.

Perhaps time to forget the use of a drill altogether?

Tapping The End Of A Single Branch Or Multiple Branches On The Same Tree

Perhaps the best practice is to abandon hole drilling altogether. At the height of sap flow, from a mature healthy tree with a large crown, a single branch cut towards the end where the diameter is approximately 1 cm across, can yield up to 1 1/2 litres of sap in 24 hrs if a piece of tubing is tightly fitted over the end and run down into a bottle (In the most basic form of this method, you can skip the tubing, an just stick the cut branch end into a hole made into the bottle top.

If doing this, make sure it’s a really tight fit, and scrape all the outer bark off for a few cms from the branch tip to avoid getting bits of bark debris in the bottle when pushing the branch into the top). Four or more tubes running from different branches on the same tree can collectively yield more than a single drill hole in the same time. In addition, these can be cleaned with boiling water and birch tar ‘n wax sealed. Even without the clean and seal, it seems possible, if not probable, that this more gentle and less invasive method is likely to be less harmful to the tree than hole drilling.

No tube. Just cut and clean the branch of bark and tightly fit into the bottle lid.

The tubing doesn’t need to be this long. 10 cm is long enough, and it can hang from the tree, as long as you have ensured it is a tight fit.

Cut cleanly with a knife or small saw, indeed using a small saw is far easier. Ideally select a branch angled downwards, although if the tubing fits very tightly the angle is less important.

One downside to branch collection is that on the rare occasion when the temperature plumets from 12 degrees celcius to -1 over night, the sap in the tube freezes and collection grinds to a halt! On the other hand, spiles can freeze up too, although in my experience, in such conditions the branch tap tends o stop flowering before the trunk tap.

Naturally occurring branch collars at the point where branches change direction, are a way trees partition off, compartmentalise and isolate infection. There can be many branch collars between where you cut for sap – and the main trunk. Which means many defence barriers against disease:

“When woody plants naturally shed branches because those branches are nonproductive, usually from lack of light reaching them, these lower branches typically die back to the branch collar. Insects and fungi decompose the dead branch, and it eventually falls off, leaving the exposed end of the branch at the point of its attachment at the branch collar. This arrangement helps to resist the spread of decay organisms into the parent stem or trunk during the time it takes for the increment growth of the trunk to seal over the dead branch stub.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Branch_collar

These fantastic trees in my garden produce about 6 litres of sap every 24 hours into the 4 2 litre bottles I’ve attached. Looking about the ground below, one can see the brances that the tree has naturally disgarded are the same size, if not larger in diametre, than the ones I’m cutting.

Naturally isgarded branches.

Another fantastic tree.

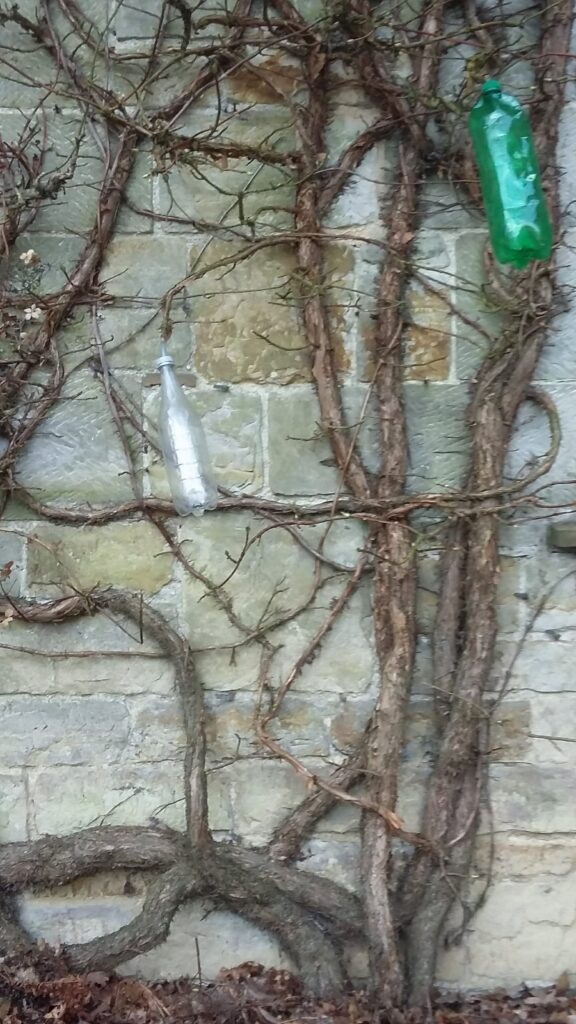

Can you spot the four bottles?

Using green bottles makes them easier to find.

If you do, however, feel peturbed about leaving a branch dripping after sap collection, you can always try and seal the cut.

Birch bark tar making, wound sealing, and King Canute-style holding back the relentless sap tide.

Collect lots of birch bark from well rotted fallen trunks. Stuff tightly in a large round (see picture) in a cake/biscuit tin that you’ve made a hole in (use a nail and hammer – hammering from the inside so direction of hole directed outwards). Fit the lid on tightly. Dig a hole to snuggley fit a tin can in. Place cake tin on top. Make a fire on top of this and burn for 2 hours. This will dry distill the

tar/oil/pitch out of the bark. Remove the tin from the hole and place on hot embers to boil and reduce the tar by half the volume. Note: the jar of oil below is floating on water that was also in the can. That’s because the bark was damp. If fully dried first there will be no water.

I made a clean fresh cut 6 inches back from the original cut, sterilized with freshly boiled water and brushed on the thick tar.

The above attempts to seal exposed branches with tar were my attempt to honour the tree by going through a process requiring dedication and best intentions. In practice, my optimism proved somewhat naive. Sap flow is powerful and is very hard to stop! In the end I had to combine traditional and modern materials. Two methods that worked to stop sap flow 8 out of 10 times: Moulding a piece of tar (consistency of cold chewing gum) into a piece of modelling clay, and pressing tightly on the branch (tar on its own only worked to stop the flow 2 out of 10 times), or mixing the tar (when still hot) with wax. More experimentation required…

Finally, before moving on to working with the collected sap, here are a few other interesting tapping techniques from around the web. Personally, I prefer the branch collection method now, but at least the following demonstrate an impressive (but not difficult) degree of skill and a willingness to work with natural materials:

- Alexander Yerks’s dual-purpose beech wood external groved tap and sap collecting hanger.

- Ray Mears (collecting sap for his mint ice cubes to go in his single malt)! Similar technique to Alexanders.

- Lonnie of Far North Bushcraft’s green willow tap, creating a central hollow using just his knife.

- Maurice Clother’s manual lathe made oak wood taps and plugs.

- Fergus Drennan’s ash bark tubing branch collection method.

Amazing post with so many useful links & info. Thank you!

Thanks for such a comprehensive post on this! When your out prospecting for Birch sap do you cut a branch at 1cm thick and see if sap run out? Or will a small amount of sap run from a thinner twig when cut, then confirming if its worth cutting a larger branch? Just want to minimise the damage done to trees when working out when the best time to tap them is. Thanks!